The best way to learn about the Georgia Grasslands Initiative (GGI) is to sit down and read the website. I did that since I love community science. The website was informative, but I didn’t expect the language to be so poignant.

Here’s the part that got to me:

What happened to Georgia’s Grasslands?

“Grasslands in Georgia have been lost to our collective memory. They disappeared because of fire suppression across the state, lack of disturbance historically by elk, intense land use history, and reforestation with closely placed trees creating a lack of sunlight in the woodlands. A few precious examples do exist. Help us find small, relic sites along roadsides and rights of ways, in old fields, and mature woods.”

Before reading about GGI, I wasn’t really aware of the problem. Now I know that grasslands cover about one-fourth of the world, support flora and fauna, improve soil content and prevent erosion, help clean our air by pulling out carbon dioxide and releasing clean oxygen. Also, I know that grasslands are in decline here in my home state of Georgia, mostly due to development. Georgia’s Piedmont region, highlighted with the green stripe in the GGI logo below, is where Georgia’s grasslands have historically flourished, but you can see from these images that things have changed.

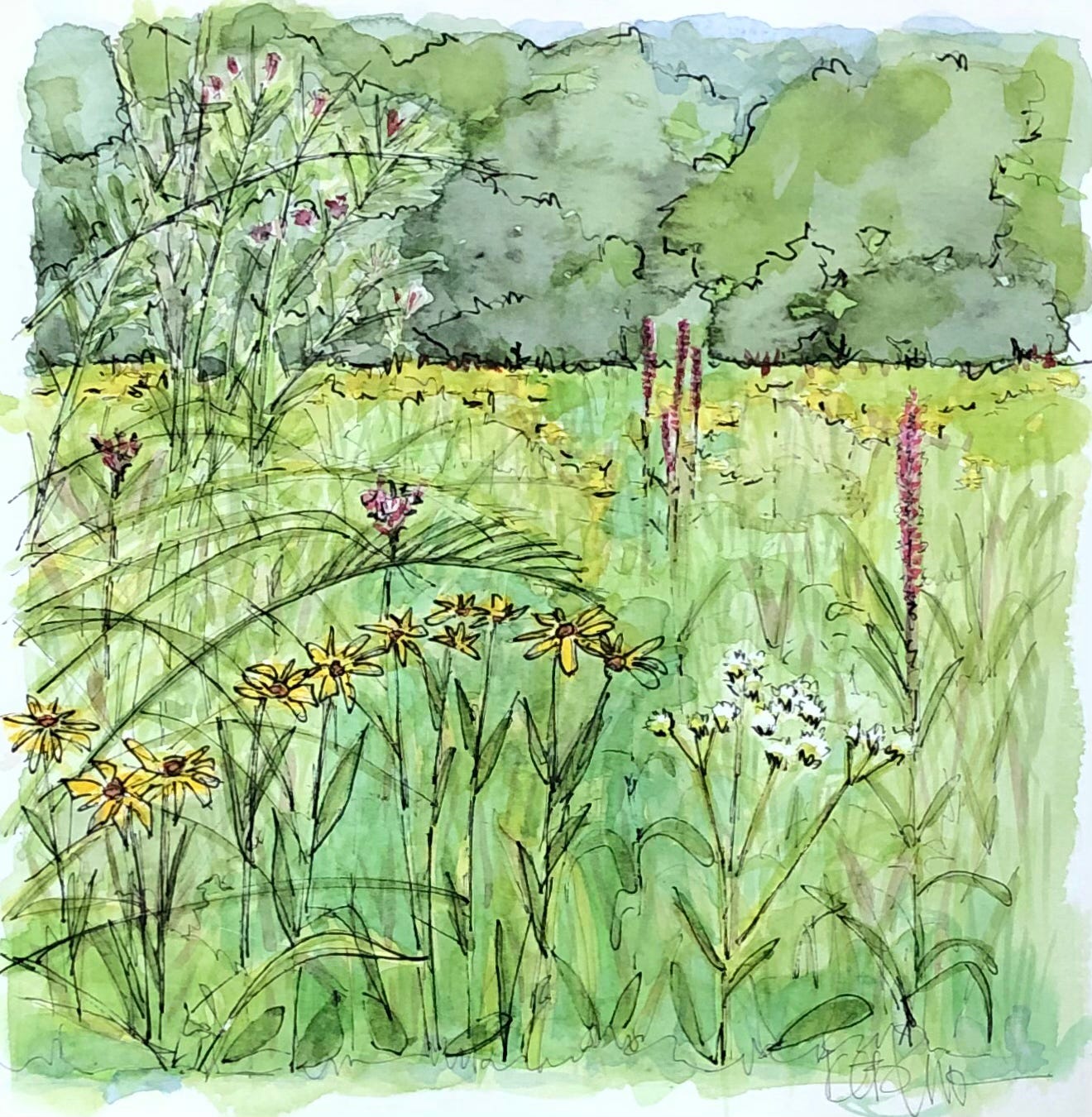

Grasslands are beautiful, and endangered

In March, I interviewed Phil Delestrez for the North American Butterfly Association issue of this newsletter, and he began my education about grasslands when he said, “One of my first jobs was as a seasonal park ranger at Rend Lake, Illinois. I loved the beautiful prairie grasslands there and learned a lot about how to manage the landscape in ways that are beneficial to insects, birds––everything really.” After we talked, I began looking at images of prairies and meadows at Rend Lake, and at other areas around the world, and was always impressed with the stunning vistas I’d find. Now, after learning about the local GGI efforts, sponsored by the State Botanical Garden of Georgia, I finally had my chance to get involved via community science.

Taking Grasses’ Picture = Not That Easy

Before I planned a field trip for Fred and me to go document grasses for GGI, I spoke on the phone with Will who has worked with the project for the past few years. “We’re trying to get the word out about GGI,” he said. “Grasslands have been lost in Georgia, but I’m always encouraged to see some plants cling on, along roadsides and in open fields. We love it when birders, students and just anyone who cares about the environment wants to pitch in and take some pictures for us. We ask people to upload their images to our special project page on iNaturalist.”

“Sign me up,” I told him. “iNaturalist and I are old friends. I know all about how the app works, the regular observations, the research grade ones, the special projects, the connections to science. I love the way research grade data are funneled to professionals who can aggregate data that can be used as a foundation for fact-based decisions. I’m aware and ready to go.”

Rain was forecast for the Friday we picked for our GGI field trip. I told Fred it says 100 percent rain, but he who does not get ruffled by the weatherman said, let’s go anyway we’ve got rain gear. The truth was that we planned a two-day trip which would include, besides community science for GGI, dinner out with friends and a full-day bike ride––and neither of us felt like cancelling any of it. So, we headed off on adventure fully prepared to be wet for most of day one.

As directed by Will, we headed to the section of the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest located southeast of Athens, Ga. Once we got there, we drove up and down narrow backroads and muddy dirt lanes seeking roadsides filled with grasses and wildflowers. Will had said that if I could take a picture of a grass species that was flowering, even a small bloom at the top would do, it would be easier for me and easier for an expert to identify the species.

We started our work on the west side of the forest. A typical grass observation went like this: Rain poured while we parked alongside a forest road where we could see, through our blurry windshield, some wildflowers growing in and around the ditch. We’d get out and roam around a little, then I’d get to work, sinking low into the damp to single out some blades, stems and blooms for photos. It took a while.

The grass world keeps things tight. I would separate stems from leaves, while also documenting whether the leaves changed shape near the ground, and if they did, I’d take a picture of that too. I felt it was important to keep the same components of the same plant together, and not get it mixed up with a neighbor. Sometimes I’d line up a stem along my palm and forearm to better define it and have a solid backdrop. Other times I’d take an aerial, top-down photo of a bloom. Always, I worked to keep my phone relatively dry and steady in all the all the moisture.

After a while, Fred was like, you’re taking a long time, but I said I need the angles, so he got back into the dry car and left me to it. We were deep into the forest, no houses, no cars, but the work wasn’t bad because it was peaceful out there in a space so different from my everyday suburban surroundings.

We would have driven right by these grasses and wildflowers with no more than a glance, I thought. I want to remember this. Here I am, paying close attention.

I can’t remember how often I tripped and tangled in the confusion of grass blades and stems, but before long, my wet feet and legs began to get more of my attention, so I jumped back into the car, and we headed to the next place.

Our next stop, four miles deeper into the forest, was a place called Scull Shoals, an area of some repute down at the dead end of a dirt road, Forest Road 1234. The article I’d read about this place had darkened my thoughts toward it because words like “haunted” and “ghost town” were used to describe it, while suggesting the name Scull (skull?) may have come from the fact that human skulls had been found there. But, happy surprise, Scull Shoals was a delight. I was driving when we got close, and I immediately slowed my roll so we could absorb the sight of abundant grasslands, by far the most we would see all day, in this wide forest opening.

“So amazing,” I said as we drove in and parked. “And, lush. Look, I found’ bashful wakerobin."‘ What a great name.”

“Yes,” he replied. “This big clearing is a really nice surprise.”

“And not one bit scary. The grass is too good for this place to be troubled.”

We walked around for more than an hour in the area around Scull Shoals, the rain our constant, almost unnoticed, companion. The forest opening meant that more sky light got in, which helped the wall-to-wall landscape of grasslands and wildflowers bloom. Even in the rain, the space was illuminated from above, allowing us to see better than before, and for me to take better pictures. In the early 1800s, a mill town thrived in Scull Shoals, with 500-600 residents. Unfortunately, the buildings were constructed on a flood plan and extreme flooding over the years left the whole town mostly buried in silt. I could see remnants of a four-story brick warehouse, and I tried to imagine the rest, the houses, a post office, a toll bridge.

I took a dozen pictures for GGI at Scull Shoals. There was no cell service here, but I checked iNaturalist and could see that my images looked good, ready to be uploaded later. It was time for lunch. Back in the car, which was getting mud-tracked and damp on the inside as well as the outside, we unwrapped the Wendy’s we’d wisely picked up back Greshamville. Picnic time. Today we’re serving burger and fries for Fred, roast chicken salad in a bowl for me. As I sprinkled sugared pecans on top of my salad, I imagined the circle of nature around our car as a bowl too, a dark green organic bowl of good health. Nothing iceberg-y about it, I thought, looking down at my little salad, which actually looked quite appetizing despite its pale lettuce base.

“Food is always so good when you’re camping,” I said, taking a crunchy bite.

“Yet, we’re not,” Fred said.

“Well, not fully camping, okay. But we are outside and my lunch tastes amazing, so—it’s all good, it all comes out in the, uh, wash.”

When I got home from the trip, I sat down to look over the GGI results to date and found that the grasslands species count is now up to 2,227. I like nature names, so for my amusement and maybe yours, here are some of the grasses documented so far: lyreleaf sage, common blue violet, sourwood rue anemone, purple passionflower, sparkleberry, bashful wakerobin, and the late boneset. Also, there is the helmet skullcap, black elderberry, cross vine, fan clubmoss, tiny bluelet, ebony spleenwort, Indian pink, common jewelweed and many more.

While on the subject of names, it is worth knowing that around the world grasslands have different names. In Africa, they are called savannas; in the American Midwest, prairies; in South America, pampas, and in Central Eurasia, steppes. No matter what the names, one of the things they have in common is an impressive root system that helps prevent erosion.

The lawn question

There is a question about the difference between lawn grass and grasslands that I keep being asked, so I want to share this answer that comes from a few sources: The key difference between natural grasslands (a meadow or a prairie) is that it is made up of native grasses and plants, whereas lawns are made up of grasses that are there for their durability and, in most cases, are not native to the area.

And finally, a suggestion from Wildlife Heritage gets the last word on grass this week:

“The next time you drive by an open field, give it a second look and be happy to see the grass blowing in the breeze. Whether it is being used for grazing or simply sitting as it is, the fact the land remains as grasslands is a good sign.” -Wildlife Heritage.

Earth Day is Saturday, April 22.

Upcoming:

City Nature Challenge is an annual international biobitz that mobilizes people to document urban biodiversity and share it with science. Using the iNaturalist app is a key part of participation in this event which runs from April 28 to May 1. You can check at the website to see whether your city has registered. If not, you can still join in by being a part of the Global Nature Challenge.

Pam, I am enjoying yiur newsletters so much. I learn a lot and appreciate your conversational writing style. Keep it up!

Wendy

Learn something new everyday. Now my eyes will be open more and aware as I drive anywhere to notice the grasslands. Thank you.