Lonely? Not Me. Not Today

A big old snapping turtle---and a little background research---was a sure way for me to mitigate species loneliness recently.

“We have built this isolation with our fear, with our arrogance, and with our homes brightly lit against the night.” - Robin Wall Kimmerer

This summer, Fred and I embarked on a cycling trip along the Cape Breton Trail in Nova Scotia. Our two-wheeled journey around the northern coast of Cape Breton Island was incredible, made even better by one of our ride guides, a young biologist and naturalist named Cherise. She and I cycled together as often as possible, always wanting to make pit stops for the butterflies, or the asters, or the shorebirds we saw along our way.

I loved every moment, but the highlight came on our last day together when I pulled out my copy of Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer, the book I’d been reading in my spare time.

"I'm reading that too!" Cherise exclaimed, and we launched into an enthusiastic discussion about the sections we loved most. We realized we had both been reflecting on Kimmerer’s writing about “species loneliness.”

A biologist and Indigenous teacher, Kimmerer explains in her book that species loneliness is “a profound human sadness that stems from our estrangement from the rest of creation.” She describes how, when humans separated themselves from nature by living in homes surrounded by walls, technology, and capitalism, we became like visitors in the very environment that was once our home.

As Kimmerer poignantly writes, “We have built this isolation with our fear, with our arrogance, and with our homes brightly lit against the night.”

However, Kimmerer reminds us that it’s not too late to repair this broken connection, and reading her book helped me understand the many ways it can be done. I'm now in my second year as a community scientist, writing about my work, and this focused time has deeply strengthened my bond with the natural world.

Just last month, I had an up-close encounter with a massive snapping turtle. I found him at the park I visit most often near my home in Atlanta. After a hot, dry summer, we’d just had a big gully-washer of a rain (right before Hurricane Helene hit), so I headed down to see how much the creek had risen. As I wandered around, I spotted the snapping turtle up on the park’s driveway, struggling to get back down into the water.

Luckily, the Amphibian Foundation offices are at the park and an employee drove by. I flagged her down and she was quick to display her expertise and confidence with this muscular species.

"She's a big one," Ms. Turtle Expert said.

"But wait,” she added. "Actually, he. That’s a penis down there.”

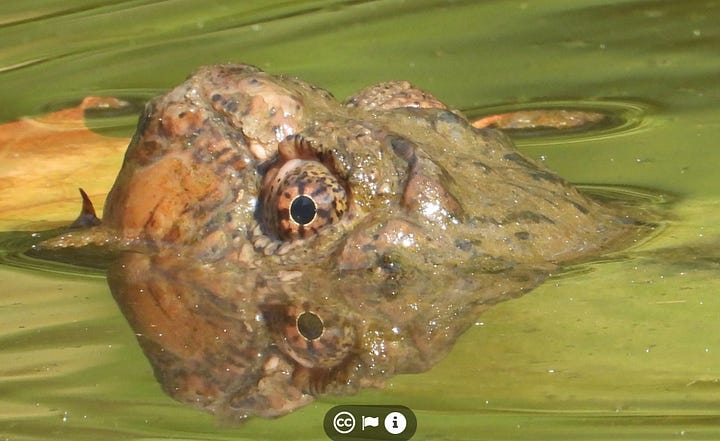

Amphibian Foundation employees regularly tag local wildlife for research, so that happened the day we discovered the snapper. We guessed that he had been washed up, down, and all around by the flooding creek. At the time he was stuck on the park’s driveway, trying to squeeze through the guardrails. After being tagged, he was placed closer to the creek and hurried on his way. I loved getting the close up views.

Snapping turtles are known for their aggressive nature, however, the truth is they are calm and docile in the water. On land they can be a bit more feisty and will flaunt their powerful beak-like jaws, and highly mobile head and neck. The Latin name for the species is Chelydra serpentina. Serpentina = snake-like.

Side-eyed and stealthy.

When searching for a meal, snapping turtles will often bury themselves in the muddy bottoms of rivers, lakes, and ponds, leaving only their eyes and nostrils exposed. They lie motionless, waiting for something edible to pass by, then swiftly snatch their prey, according to Animal Diversity Web. They aren't fussy eaters—if they can catch it, they'll eat it. As omnivores, their diet includes fish, birds, aquatic invertebrates, amphibians, and a wide variety of plants.

Occasionally, they even eat other turtles, decapitating them in the process. It’s a grim reminder that these turtles are undeniably tough creatures—but understanding their role in the ecosystem makes that toughness easier to appreciate.

Reducing loneliness of all kinds? An undeniably good idea.

When I think about species loneliness, I see it as something that elevates my time outdoors, adding layers of meaning to each moment in nature. Lately, the passing of seasons has made me wonder—how many more autumns do I have left? 10? 20? 30? None of us really know, but like everyone, I want to make the most of that time. To be less lonely—not just with people, but with all the life we share this planet with—feels like a worthy pursuit.

After learning more about the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina, and encountering one up close, I felt a new sense of connection. Being a community scientist helps deepen this bond. I’m an avid participant in iNaturalist, the world’s largest and most powerful community science project. When I logged in to search snapping turtles, I found 81,723 common snapping turtles had been documented. As I wandered through the October 2024 photos, I realized each sighting is a moment of connection—not just with the species, but with the idea that we all share a fragile, interconnected web of life.

Always an inspiriation! I have been watching the tadpoles grow in the frog pond in my front yard, amazed that it takes three to four months for them to transform into tiny frogs. Thank you so much for your work as a community scientist!

Loved the article but the bike trip was impressive. We have only driven that route.