Seeing Red in the Diamorpha Fields of Arabia Mountain

A walk with an expert and iNaturalist

Last week, I joined a group hike to see the endemic Diamorpha plants in full bloom at Arabia Mountain. The outing was a chance to do community science and see beauty. Getting ready that morning at home, I put on my sunscreen and thought I had a good clue of what was to come: the fusion of nature’s soft side––little fragile flowers––blended with nature’s tough stuff, a weathered granite mountain. Yet when we got out to Arabia an hour later, I felt my hopes for the day rise even higher when our hiking guide welcomed us with two evocative sentences:

"The mountain is having a moment. I can’t wait to get up there and show you.”

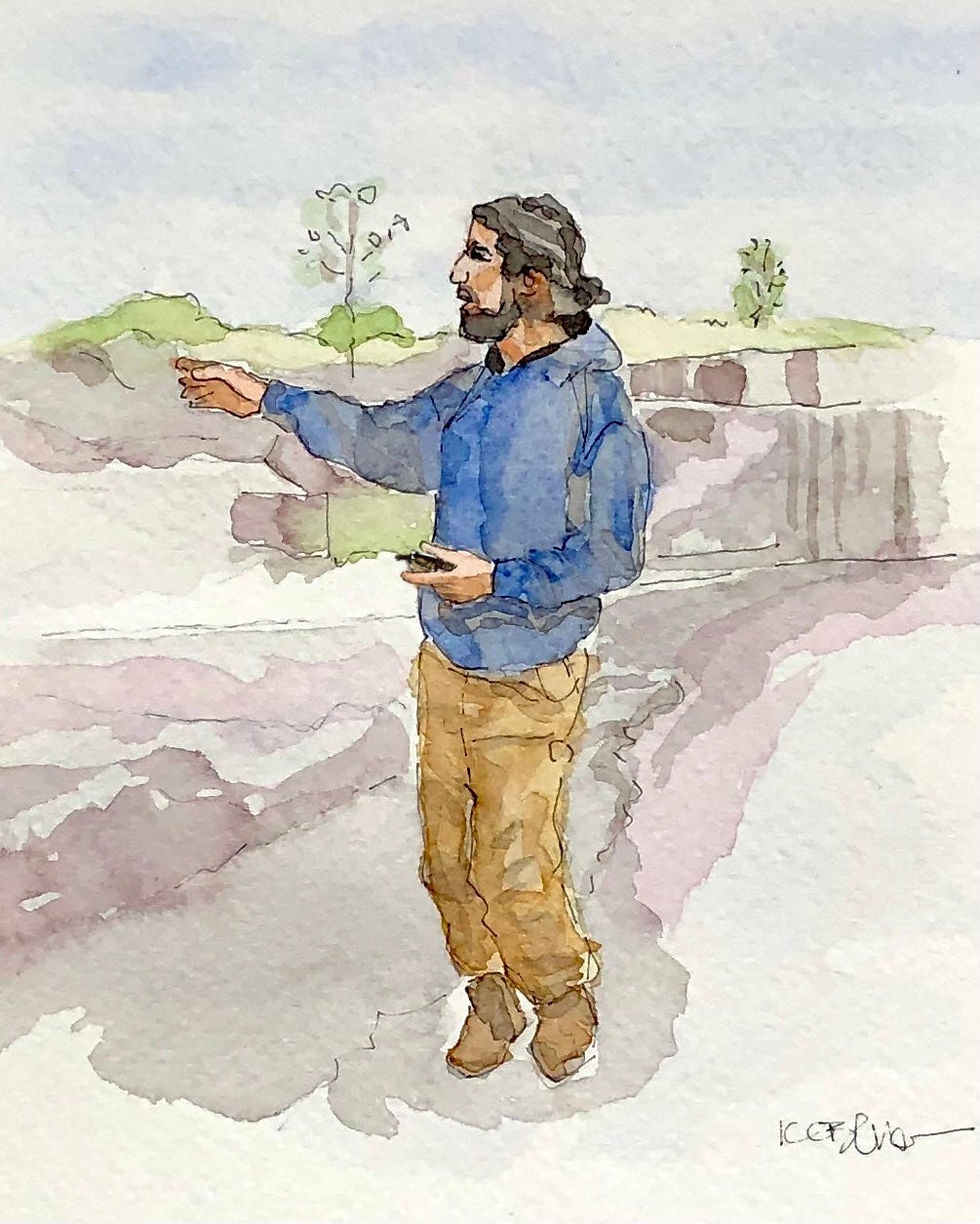

Speaking was Robby Astrove, a Park Ranger at the Davidson-Arabia Mountain Nature Preserve, who goes by “Ranger Robby.” The mountain has been his workplace home for more than 10 years. He is protective of the 2,200-acre natural landscape and reminded us to “stay on the gray” before we began our two-mile outing up and over the mountain. Arabia Mountain is not particularly high, only rising 955 feet up to a flat-ish tabletop ‘peak’. “We’ll stop and talk a few times, but you’ll have time to wander,” he said. “You are here at peak Diamorpha blooming season. The timing couldn’t be better.”

There are many ways for teachers to teach and students to learn. Ranger Robby has led hundreds of trips along the trails of this granite mountain over the years, and many of those groups were of the kid variety, out on a good old-fashioned field trip. He has developed what seemed to me to be an ABC mode of teaching, when A is your content, B is your visual and sensory, and C is the teeniest suggestion of a life lesson. This method probably works great for most of the kids he speaks to, and his light touch that early spring day was perfect for me as well.

What you get in 3 stops with Ranger Robby when Arabia Mountain is having a moment.

Stop 1. We’d reached the first of what would be many red circle patches of Diamorpha blooms on Arabia. Looking around, I was amazed that anything could even grow up here in all this rock. One biologist, describing plants that grow in places like this, wrote: “There is nothing on these (rock) outcrops that a normal person would call soil.” It was true. There was only grit, sand, gravel and rock underfoot. Ranger Robby told us that Diamorpha is a winter annual plant. Every year it gets started in the fall and winter as little pea-sized balls of green, then later turns into red stems and leaves. The leaves look like balloons, I thought. Ranger Robby encouraged us to get down low to scrutinize the diminutive two-inch forest at our feet. So down I went, knees to rock, and looked into a Diamorpha world. Right away, I started imagining what ants would see running through the place. With their multiple eye lenses, it could seem wild, like maybe is the world’s on fire, but wait maybe it’s okay because there’s party balloons and and a soft marshmallow cloud sky?

Ranger Robby: “Diamorpha is strong. We have these big patches of it all over, but then you’ll see volunteer sprigs of it just growing up out of a crack in the rock. So, watch your step. Over and over, these little guys just seem to be saying: I’m going for it, over here, or over there! Sometimes I think, can I be resilient like that?”

Stop 2. Further up the mountain, rock depressions had created little wetland pools which gave us something else to wonder about. Our “looking-closer” skills were better now, so right away many in our group squatted down to check out the still surface of the water. Green. Dark greens were now added to the day’s color palate, and we listened as Ranger Robby told us what we were seeing. I loved the names, especially Snorklewort, so named because of how there’s a pair of tiny oval leaves floating on the surface of the water grabbing fresh air for the plant stem below. Some of the other plant names we heard, Pool Sprite and Black-spored Quillwort, also captured my imagination. As I took photos for iNaturalist and community science, I thought back to all the newsletters I’ve written this year, and how so many nature names please me by being a touch weird with generous use of hyphenation and compound words.

Ranger Robby: “Algae and fungus are working together all over Arabia. Here’s how I explain the relationship to the kids. Algae says, hey I’ll be the chef and cook all the meals. Fungus says okay that’s cool. I’ll give you a place to live. That’s symbiosis. I ask wouldn’t it be nice if people could cooperate like that?”

Stop 3: Arabia Mountain hasn’t always been a beloved natural area. Eighty years ago, the area was the site of a thriving quarry business and the frequent roar of dynamite blasts disturbed the peace for miles around. At this stop on our hike, I could easily see the straight-line cuts in the rock where slabs of granite had been removed. There were plenty of Diamorpha around too, some of them growing right along the gravel-filled lines of the rock cuts.

Ranger Robby: “When I first started working here, I didn’t like this area where you can see evidence of quarry work. You wouldn’t catch me in this area. But now, I appreciate it. It is one of the prettiest places on the mountain. Look at all this Diamorpha. All the cutting left behind more sediment, the gravelly bits. More plants are growing here. Nature is slow, a performing art, like a symphony. Each month, there’s a different solo. Things unfold in due time. I’ve come to appreciate the slow ways of nature, and everything that is here at Arabia.”

When the hike was over, everyone said thanks and went their separate ways. I felt lucky to have had the experience to learn about the ecology of Arabia in such a delightful way. I’ve taken a handful of nature hikes with experts this year and each time am amazed at how much I learn from the stories, experiences and data they share. What a way to learn, outside and strolling around with not one thing feeling heavy, no textbooks and no tests, to dampen the spirit. The free Arabia Mountain hike was organized by the Georgia Conservancy, whose mission is to protect Georgia through ecological and economic solutions for stewardship, conservation and sustainable use of land and its resources. You can find more events at their website.

Georgia Grasslands Initiative (GGI)

A bonus to the Arabia hike happened when we met Anna, a UGA environmental sciences PhD student who was collecting data for a research paper. Ranger Robby invited her to tell us about her work, and as she did she included community science, saying, “I use iNaturalist all the time.” Anna then told us about a special Georgia-focused project. “The State Botanical Gardens of Georgia is doing a project to document native forest species on state lands, all through iNaturalist. You should check it out,” she added, before turning back to her work. Later, at home, when I read the Georgia Grasslands Initiative (GGI) website, I learned this:

Our roadsides hold relics of lost grassland and woodland habitat that have been declining since European settlement. Georgia once had expanses of open forests with widely spaced trees and a full understory of wildflowers and grasses. We need your help finding and documenting these sites with sun-loving wildflowers and grasses. If your passion is bees, butterflies, birds and other wildlife, help us find these sun-loving plants that support them.

iNaturalist was created by a partnership between National Geographic, Microsoft, The California Academy of Sciences and Google maps.

I gotta go.

I’ll be attending a Urine My Garden (How & Why to Fertilize with Urine) Webinar next week. The webinar would have relieved me of $10, but it is free due to my wise use of the promo code, PEE4FREE. More later.

Also:

April is Citizen Science Month. Learn about opportunities, classes and projects, including more thinking-out-of-the-box ideas like Urine My Garden, at SciStarter.

Georgia Audubon has a helpful community idea that is the birds:

It's Time to Dim the Lights for Migrating Birds

Spring migration has officially begun, and we encourage you to reduce or eliminate outdoor lighting through May 31 to help our migrating birds. Can't turn your lights out for that long? Consider signing up for our Lights Out Alerts on nights of peak migration (about 10 per migratory season) when reducing outdoor lighting will help the most.

What an informative article. I felt like I was there walking through the party balloons of the Diamorphia.