A beluga has a hashtag. That's not good.

Another story of human encroachment on the natural world.

In a distant ocean, a beluga whale was born. The sea sparkled as the newborn, a soft ball of life, entered a vast, salty world. The mother, a marine mammal, glimmered beneath the waves, her weight matching that of a 3,000-pound hippopotamus. The baby, 140 pounds, was as light as a kangaroo, similar not only in size but in shade of gray. Together, mother and newborn flourished in the ocean’s rhythm, remaining closely bonded almost always touching as they navigated their everyday lives. Two factors fueled the little one’s growth: nourishing milk from its mother and the proximity to her that provided safety and wisdom.

As the years passed, the young beluga, now white, felt the calling of independence. Belugas, known as the brainiacs of the sea, sometimes find themselves looking for entertainment and are drawn to boats and the people in them. It happened that way with our young friend, who would eventually be dubbed Hvaldimir by some humans. He left his mother’s side, drawn to the brown shorelines, or to the company of humans in their boats. People usually showered him with affection, petting his sleek white skin, now pure white, and sharing herring and octopus snacks. One day, humans approached Hvaldimir, ensnaring him in a net. While trapped, they secured something tight around his ribs, a mystifying tightness. However, he was treated with care and fed continuously, soon released into the wild waters once again. There he went into a frenzy of rolling and tumbling in the current, trying for days and days to shake off the strange sensation.

Eventually, the weird feelings became normal to him, and life resumed as usual. He continued his adventures—swimming with other whales, hunting for food, and occasionally seeking boats or places where humans congregated. One day, he approached people in a boat once again, only to be caught once more. This time, the now-familiar contraption around him disappeared, and Hvaldimir was freed again. Suddenly, the urge to move with speed overcame him and he swam fast and far. Today, he is 14 and far—too far—from his original home waters. His story continues to unfold, and a big part of his tale includes humans. Unbeknownst to Hvaldimir, his interactions with humans have altered him greatly in ways that are endangering his life.

Hvaldimir’s tale? Rooted in the real world.

Hvaldimir's saga may evoke the enchanting allure of a beluga gracefully navigating between the realms of humans and whales in the expansive ocean but actually—and sadly—the tale is firmly rooted in the real world. Today, numerous verified news stories reveal that Hvaldimir exists, and that the reported "tightness" on Hvaldimir was, in fact, a harness concealing what is believed to be a spy camera that was automatically capturing images for one country to spy on another. 1 The harness has been removed, but still Hvaldimir faces considerable peril as he has grown accustomed to human interactions and less attuned to the challenges of his natural environment. The intrusive incidents the whale has endured, and the news reporting about them, has sparked the rallying cry captured in the hashtag #savehvaldimir.

The story serves as a stark illustration of human encroachment on the natural order of the world. It resonates deeply with me, and the decision I made in late 2022 to become a community scientist. I’ve witnessed so many ecological shifts in Georgia, such as prolonged growing seasons, shifts in flower bloom timing, and in bird migrations. Altogether, these changes fueled my desire to delve deeper to learn what is going on and to share what I’m learning with others. Reading about the plight of Hvaldimir made me ask: are belugas endangered or threatened? Also, I realized I was fuzzy on the terminology of species protection, not clear on what it means to be on the red list, and felt unsure about the basics of our country’s Endangered Species Act which just celebrated a 50th anniversary.

Briefly, the lowdown on the ESA, the IUCN and how the belugas are doing.

First off, know that the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the International Union for Nature Conservation (IUCN) are distinct mechanisms aimed at similar goals: addressing the conservation of endangered species. But there are major differences in scope, purpose, and application.

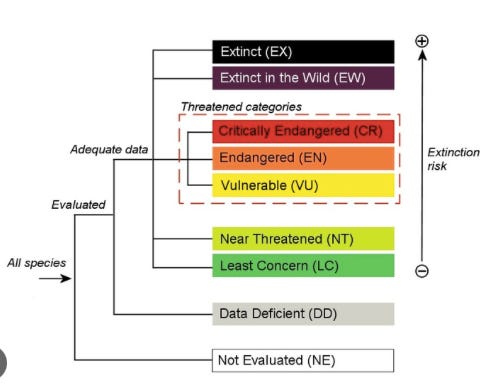

The IUCN and the IUCN Red List are global in scope, assessing the conservation status of species worldwide, transcending political boundaries. Information gathered by IUCN scientists and researchers often informs efforts at the individual country level, and most major countries around the world have their own lists and species protection laws. The IUCN red list categorizes how close a species is to extinction using nine groupings: not evaluated, data deficient, least concern, near threatened, vulnerable, endangered, critically endangered, extinct in the wild, and extinct.

The U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) is a federal law that provides a framework for listing, protecting, and recovering imperiled species at the national level. The program conserves threatened and endangered plants, animals, and habitats in which they are found. Since it was passed with bipartisan support in 1973, the ESA has become one of the world’s most powerful legal tools for protecting species at risk of extinction. The act has a stellar success rate, saving 99 percent of species it protects from extinction. Five well-known success stories are: the Bald Eagle, the American Alligator, the Grizzly Bear, the Whooping Crane, and the Green Sea Turtle.

Using the beluga as an example, I found that the IUCN and ESA guidelines are closely correlated. At the IUCN, beluga whales were considered vulnerable in 1996, changed to near threatened in 2008, and changed again to least concern in 2017. However, due to habitat challenges in the Cook Inlet of Alaska, the belugas in that area have been assessed separately and listed as critically endangered on the red list. At the ESA, the Cook Inlet Beluga population was found to be depleted in 2002 and was listed as endangered in 2008.

Presently, the global beluga population ranges from 150,000 to 200,000, predominantly inhabiting the Arctic Sea and its adjacent waters. The Cook Inlet population of Alaska has dwindled significantly over the past four decades, plummeting from an estimated 1,300 belugas to a mere 330 at present.

Hvaldimir Today

No one knows for sure where Hvaldimir was born or where his life’s journey has taken him. He has been spotted in Norway’s coastal waters, then more recently on the southwest coast of Sweden. That’s where observers say he is now. The warmer Swedish waters, not a natural habitat for a beluga, spell trouble for him, plus there is heavier boat traffic and fewer fish. Reports are that he has lost weight over the years.

A Norwegian conservation nonprofit is collaborating with Norwegian authorities to ensure the safety of Hvaldimir. The immediate plan is to reduce Hvaldimir’s connections to humans, and eventually create a 500-acre marine reserve in northern Norway. This reserve would serve as a rehabilitation center for Hvaldimir as well as other whales in trouble. Eventually, the hope is that Hvaldimir would be reintroduced to a natural population of beluga whales living in their natural surroundings.

OneWhale, an organization with the motto, “Advocating for Hvaldimir since 2019,” accepts donations.

Harness-wearing beluga whale believed to be a Russian spy popped up in Norway. Business Insider.

This famous ‘spy’ whale likes people. That could be a problem. New York Times.

An alleged Russian spy whale is in Sweden. NPR.

Suspected Russia-trained spy whale reappears off Sweden’s coast. The Guardian.

What a wonderful post! Thanks for sharing.