Community Scientists = People Who Try

Learning to tell the difference between a carpenter bee's "shiney hiney" and a bumble bee's regular "fuzzy hiney"

Today, I came across an inspiring story written by a lepidopterist based in the San Francisco Bay area. He initiated a project aimed at safeguarding a particular endangered butterfly species in his region. Buried deep in his article was a comment of his which sounded profound to my ears:

“I always say in my talks I just want to be a part of people who try.” -Liam O’Brien.

These words may seem straightforward but they carry significant weight, especially in the world of community science. Just being “people who try” is a big part of what it means to be a community scientist.

Fact: While all pollinators are facing significant threats, an analysis led by the Xerces Society, and coordinated with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) North American Bumble Bee Specialist Group, indicates that more than one-quarter of North American bumble bees are facing some degree of extinction risk.

Lately, I’ve been on a pollinator kick volunteering with Xerces Invertebrate Society while contributing to the Southeast Bumble Bee Atlas. The name Xerces comes from the Xerces Blue butterfly that was likely our first butterfly species to go extinct. (Xerces was also thought to be a good name because the “X” of Xerces makes a perfect symbol for extinction.)

This summer, Xerces expanded its Bumble Bee Atlas program to the Southeast. My friend Dana and I were excited to take the training (read about it here), and to adopt a “high need” bumble bee grid about 1.5 hours west of Atlanta where we live.

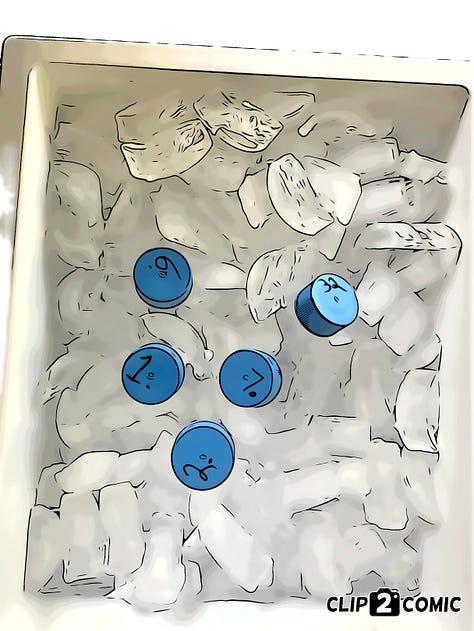

We went to our grid last week and found it had turned gold—blooming goldenrod which seemed to be everywhere, plus clumps of daisy fleabane, ironweed and other Georgia native plants. We spent a cheerful two hours at our site, walking around in the weeds, capturing (and sometimes missing) bees, cooling them off in Dana’s little Playmate cooler, then later sitting at an old picnic table to take the Xerces-required photos of each bee and doing our paperwork.

The action parts of the process were the most fun, no surprise. We loved capturing bees with our insect nets, wrangling them into vials, monitoring the bee cool-downs, then getting them out for photos and watching them fly away. There’s a little excitement involved: will I get stung on my fingers in the net-to-vial move? Will I get stung on my nose if she wakes during her close-up photos? Just like the Progressive Insurance commercials warn, sometimes things can feel like “a lot” if you are a regular community scientist who’s used to just taking still photos of plants.

Amused and confused.

The 40-second video below shows a bee waking up after being cooled on ice for her photos. She seems to be getting her legs and wings warmed up, ready for flight. Dana and I are amused, and also confused. We thought we had a bumble bee, but it was dawning on us that we probably were looking at a carpenter bee. In our Xerces training we’d learned that carpenter bees have a “shiney hiney,” and that bumble bees have a fuzzy hineys.

We caught six bumble bees and one carpenter bee during the part of our day that involved the “search-capture-put on ice” part. One bee, notorious number three, wedged herself into the vial’s blue cap and apparently stayed there during the 30 minutes in the cooler. We think she managed to stay fairly warm.

“That’s one bright bee,” Dana laughed, as I tapped and tapped the cap trying to get her out. When we finally did get her down on our paper for her photos, she was not chilled or sluggish at all. She just felt like walking, which she did, instantly making a beeline over to the edge of our table and flying away.

Fact: Bumble bees can survive in temperatures that are much too low for them to fly. To fly, the air temperature should be close to 85 degrees F.

To remind you about the purpose of the Bumble Bee Atlas, here is a little more information:

This project is a community-driven scientific initiative with the goal of collecting data for monitoring and preserving bumble bee populations. Xerces reports that numerous bumble bee species confront an uncertain fate, and we lack the necessary data to enact impactful conservation strategies, particularly on a regional level. The Southeast section of the Atlas just began this year. The fact that this is a community science effort means that participation is open to all. Xerces invites everyone to join in. While the end of September marked the end of the count for 2023, the 2024 program will gear up in spring.

Ready to get involved and be one who does something? Find a project in your area!