Bumble Bee Numbers Sting

Bumble bees get a chance to just chill at the Southeast Bumble Bee Atlas

“If you’re trying to convince us there’s not as many bumble bees as before, you did a good job.”

Speaking was a sweaty community science volunteer who had just spent a roasting-hot 45 minutes out hunting for bumble bees in a baking, silent patch of Georgia grassland on a sun-blasted morning. He was addressing Laurie Hamon, who’d just led us in a training session for the Southeast Bumble Bee Atlas.

“Yes, bee numbers are in decline,” Hamon said, looking up from her clipboard. “Our work here is important for that reason.”

Our group of 20 volunteers had just finished a painstaking hunt for bumble bees. Thankful to be back in the shade, we laid our empty insect nets aside to grab our water bottles. We sipped, people chatted. Everyone seemed disheartened to learn that 19 of us had come up empty-handed.

“But at least,” Hamon spoke up, pointing to the cooler at her feet, “we found one.”

Her royal “we” actually referred to me. I now point out (with the slightest touch of a humble-brag) that I had beginner’s luck that day.

I was the finder of our bumble bee.

Here’s the buzz on this community service offering

The Bumble Bee Atlas is a community science project aimed at gathering the data needed to track and conserve bumble bees. As of now, I am a volunteer with the project and am discovering that contributing to the Atlas will be one of my most hands-on projects of the year. Hamon is an Endangered Species Conservation Biologist for the Xerces Society which partners with the Bumble Bee Atlas project. She taught us the complete protocol for participating in the Atlas Saturday at Georgia’s Panola Mountain State Park. I especially loved hearing her speak about the bee’s “shivering flight muscles” and imagining the vibrations involved with “buzz” pollination. A portion of her comments are included here:

Speaker: Laurie Hamon, Endangered Species Conservation Biologist.

As I said earlier, this was a pleasantly hands-on project, and here’s why : catch-and-release is involved! (No bees harmed, so no worries!) Following are the 10 overall steps that will give you a good idea of the excitement you are in for, if you decide to help with this community science project that is new to our area.

Learn. You can either attend an in-person session like I did Saturday or watch this interesting two-hour training video from Xerces.

Create an account at the Bumble Bee Watch website and start thinking about the place you’d like to search for bumble bees. Xerces has been working on the Atlas in other parts of the US since 2018, so they’ve got the process down to a science.1

Go searching two times in one year. The catch-and-release part comes in as you go out and use an insect net to try to catch bumble bees. Let’s say you snag one, (Did I mention that I caught one on my first time out?), then. . .

Get that little buzzer into the pointy end of your net.

Carefully guide her into your vial and, even more delicately, screw the lid on top and don’t catch her feet!

Put the bumble bee-filled vial into a cooler with ice in. Hamon assures us that this doesn’t hurt the bee one bit.

Let the bee cool down. You want her to be sluggish for her pictures. She chills for maybe 5-10 minutes.

Get her out and start with the glamour shots. You’ll want good close up photos of her head, thorax and abdomen. A smartphone camera is fine. On a warm day, she’ll become unsluggish within 5-8 minutes, so focus.

Let her go. Release her within 100 yards of where you captured her. She’s fine.

Do your paperwork. Later, when you get home, upload your photos, add your information to the website.

Left: We have our bee. Center: She's has had time to chill and is about to become the center of attention. Right: Our bee may be wondering: Was I just here yesterday, is this deja vu?

Georgia bumble bee experiences groundhog day?

A few days after the Saturday day of training at Panola, I talked on the phone with Hamon, who was back home in N.C.

“I sure was surprised we only found one bumble bee despite all that intense looking,” I told her. “You too?”

“I would have been, except for the fact that a few of us had gone out on the Friday before and only found one. The species was an American bumble bee. And, on Saturday, you found an American bumble bee. Actually, I’m thinking there’s a good chance it was the same bee.”

“What, really? That’s crazy. Haha!” I said, chuckling. The idea of the same bee dealing with the catching and releasing humans two days in a row struck me as quite comical.

“Yes, I can’t be sure, but I have a hunch that was the same bee,” Hamon said, laughing.

Still, it is sad there weren’t more bees, I thought as we hung up.

Is variety is the spice of life?

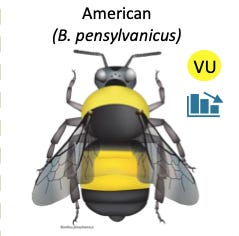

If yes, then know that plenty of zest is added our world with our 250 species of bumble bees. This chart shows Southeast bumble bee females. When you pore over the chart, please note the key, shown below, which indicates threatened species.

How adopting a grid works:

You adopt a grid in your state and make a commitment to visit blooming flowers there twice during a pollination season. The Atlas website shows where high priority grids are, and today I adopted Grid 266, near Rockmart and Cedartown, Ga., places I sometimes go anyway to ride my bike. My “season” ends on Sept. 30, so I’ll have to get cracking. (Update on 8.22.23: I visited my grid last Saturday and found five bees: one carpenter, one honeybee and three Common Eastern Bumble Bees. The weather was steamy, but I really enjoyed the work, which gets exciting each time you have a bee freaking out and buzzing like a maniac inside your net. I followed the protocol fine, but didn’t use enough ice in my cooler which resulted in not-sluggish-enough bees. I’ll do better next time.)

One out of every three bites of food we eat exists because of animal pollinators like bees, butterflies and moths, birds and bats, and beetles and other insects.—U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In closing:

I loved seeing buzz pollination in action in this three-minute PBS video that is polished and informative. The video illustrates exactly what Hamon was talking about: This Vibrating Bumblebee Unlocks a Flower's Hidden Treasure.

Is it bumble bee or bumblebee? I see both spellings out there, but I’m going with Xerces on this one.

This is the first year of work on the Southeast Bumble Bee Atlas. So come on, let’s get it kicked off in a big way. Member states are Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina.

You have such interesting projects.

Thanks again for sharing. I will be more aware of our beautiful bumble bees and look more closely when I’m out in nature. And I’ll tell them how grateful I am for their part in our existence.