Half Asleep and Fully Amazed

Learning about a migratory bird, a banding program, and long-distance travel.

One day after the election, I had a terrible night’s sleep. We had traveled to another state and were staying in an Airbnb. That first night, I had a strange dream about an alligator in the back of my car—a dream that lasted the entire night. I felt like my brain was half awake and half asleep all night long.

Overall, it was not a great way to begin a long weekend getaway. A restless night in a strange place, plus bizarre alligator dreams, left me bracing for a weary day ahead.

But partial-brain sleep for migratory birds? That’s a whole other story. Migratory birds get by just fine—thousands of miles of nighttime flying fine—with part of their brains turned off, resting.

Scott Weidensaul, an expert on bird migration and author of A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds, calls this type of sleep unihemispheric sleep and explains it beautifully in his book:

“Unihemispheric sleep, as it’s known, has been documented in marine mammals like dolphins and manatees, which must consciously take and expel each breath.

Recently, a somewhat analogous condition has been found in humans as well. Most of us have experienced a poor night’s sleep the first time we stay somewhere new; it’s common enough that sleep scientists refer to it as the first-night effect.

Scientists at Brown University and Georgia Tech found that under such circumstances, one brain hemisphere remains, if not exactly awake, at least “less-sleeping,” in their words, and more sensitive to stimuli—not fully unihemispheric sleep as birds exhibit it, but a closer match than had been realized.” -Weidensaul.

Some of these ideas came back to me this week when I had lunch with my friend, Mary. I’ve been on a committed community science journey for almost two years now, and I’ve learned so much and had so many experiences. One great experience is when a friend has a good story to share with me that connects perfectly to my interests.

Mary had a hum-dinger of a story, and you guessed it, the story is about a migratory bird. I’ll let her tell it.

“The other morning, as I walked past the large plate glass window in our house, BAM—a loud thud sounded right in front of my face. A little bird had hit the glass. My husband and I are big fans of birds, so it was sad to see it lying still on the ground.

It was clearly a goner.

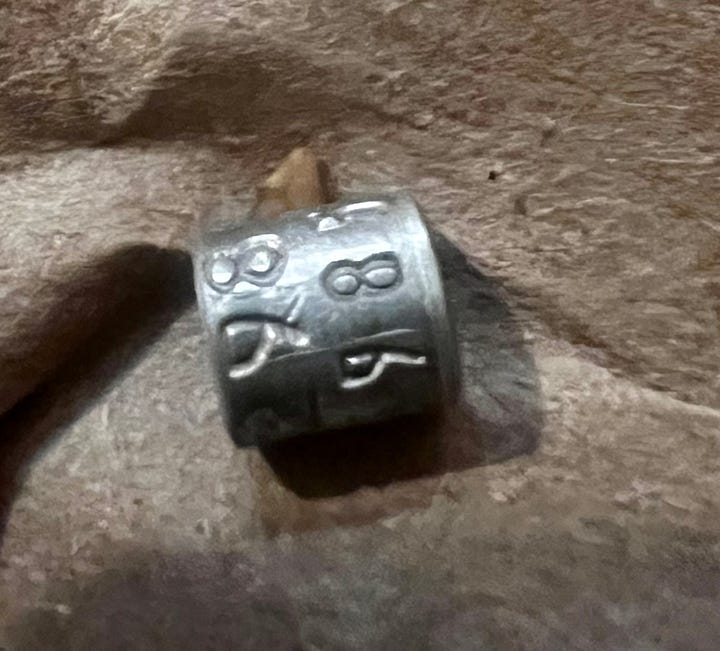

As we looked closer, my husband pointed out something unusual: the bird had a thin tin-looking band on its leg. I picked her up (later I’d learn it was a she) and realized I’d have to remove her leg to get the band off. Even though I could read the word “open” on the band, there was no way to pry it apart or slide it free.

I’ll spare you the details, but I got the band off and with a magnifying glass could barely make out the website information and ID numbers. Typing that all in my computer I had an answer almost instantly. The bird had been banded Oct. 17 near Fergus, Ontario by members of the North American Bird Banding Program. She was a fledgling, hatched sometime in 2024.

So that little hermit thrush, that little migrating songbird, had flown what something like 900 to 1,000 miles in about a month? Such a huge journey. Seems like a lot for a bird who’s almost a baby.”

I marveled at Mary’s story, and looked at all the pictures she’d taken with her phone. We started wondering about all the other birds out there, migrating on similar journeys and felt amazed at how it all goes mostly unnoticed by humans. It reminded me of something Weidensaul, the bird expert, had said in an NPR interview.1

“I remember he said sometimes people point their telescopes to the full moon during migration seasons to watch birds flying across the disc of the moon,” I told her. “Wouldn’t that be cool to see? Also, to think they are flying half asleep at times is crazy.”

“Wow,” Mary said. “Sad for the tragic end for this one. Still, I’m glad to share her data—-at least all is not lost.”

Doing our part for community science, we documented the bird by adding photos to iNaturalist, where it joined the images (and sounds) of some 43,000 of its species. I've mentioned this before in my newsletters, but it bears repeating: iNaturalist values your natural world data, even if the specimen is dead.

According to The North American Bird Banding Program, data from banded birds are used in monitoring populations, setting hunting regulations, restoring endangered species, and studying effects of environmental contaminants. In a letter sent to Mary, the program said some 60 million birds have been banded since 1904 and around 4 million bands have been recovered and recorded.

I loved Mary’s entire story—it gave me so much to think about. Her experience made me want to pick up Weidensaul’s book again to learn more about migratory birds, partial-brain sleep, and efforts to protect their shrinking populations.

After this item was published the North American Bird Banding Program reached out to me and offered two helpful sites:

Ways to reduce preventable bird collisions. Check out the Bird-Friendly Home Toolkit.

The direct link to report a banded bird is at www.reportband.gov

Thanks for reading. If you have a story that you think would make a good article, I’m all ears! Email me at pkzendt at gmail.com. On instagram find me at every_day_scientist.

very crazy she noticed that little metal tag!

Hi, Pamela! I, too, have sleep issues, and fret about not getting enough sleep. It's actually good to know there is something true about being half asleep.

Mary's experience with her little toddler bird is a lesson in thoughtfulness to all lifeforms in nature. You never know their full journey.