Early last Saturday, I joined a hiking group1 out in the woods. I was going along having a swell time looking and seeing, seeing and looking. I even used my monocular a few times to get some closer looks––10 times closer to be exact––to check out a few comely birds and faraway river features. What did my eyes see? The showy Redbuds, sparkling ripples in the Chattahoochee, some speedy Titmice, and the pale green shoots of Trilliums launching up toward the light. Our guide pointed out other sights for the eye to behold: an intact 1830s-era stone chimney, other trails we could hike, and the river access points for boats. I saw so much, but when our guide told us about the Great Blue Herons and their Great Big Nests, I realized it hadn’t dawned on me to look for nests.

I’d been nest blind.

“I assure you, the Great Blue Heron nests are huge,” our guide said. “This park is known for the Herons. Keep an eye out. This is about the right time of year for nest-building.”

The concept of humans being “blind” to something in the world has many sources. That day in the woods, I was thinking of a particular source, which came from a book about trees called The Overstory. Author Richard Powers wrote about a character who called himself “plant blind.” Later, in an interview after the book was published, Powers elaborated:

As one of the characters in the book laments, we are all ‘plant blind. Adams’ curse. We only see things that look like us.’ My compromise (in writing The Overstory) was to tell a story about nine very different human beings who, for wildly varying reasons, come to take trees seriously. Between them, they learn to invest trees with the same sacred value that humans typically invest only for themselves.2

Those huge nests, I thought. I hadn’t even bothered to look around for them.

“Some of these Heron nests are up to four feet wide,” our guide said, looking happy and laughing a little at a memory. “You can see the Herons flying by and, whoosh, there they go, another something for the nest. Not a twig either. No. I’m talking really big sticks.”

Big sticks? I remained in that place for a bit, thinking it over. As I craned my neck up, I visualized a leggy Heron up there commuting to the nest, aiming to bulk the place up for breeding season with hefty branches thick as Lincoln logs. I was missing this?

Two things felt fowl.

I didn’t like being blind to the nests, whether small or whopper-sized.

I didn’t know of any community science projects focused on nests.

Once again, I open my eyes to Community Science

My efforts to improve these issues were to return to the park, which I’ve done twice now in four days, and to do my research. On my return trips, I was better at seeing. By now, four days after last Saturday’s hike, I’ve seen a half-dozen herons and two of their nests (from far away), plus dozens of regular, everyday nests. It is a good time of year for nest-spotting as tree branches are still mostly bare.

As for community science, I’ve discovered there are two great options. Audubon offers NestWatch,3 a community science project set up to monitor the reproductive biology of birds. Participants send in nest images and often choose one particular nest to observe year-round. Right now, NestWatch is promoting a campaign to reverse the decline of helpful birds like Barn Swallows. (This is occuring in some areas, not down here in God's country––the South.) The website shows how to build a simple corner shelf in your barn or shed to provide a nesting spot for the Swallows. How are the Swallows so helpful that humans want to help them, you wonder? Barn Swallows say yum-yum to pesky insects like mosquitos, gnats and flying termites.

Second, there is Birds & Debris,4 a community science effort out of Scotland, but used worldwide, where researchers request that you send them pictures of bird nests that have manmade materials woven into them. Bird entanglement and injury is the issue under scrutiny, and the website reports that 36 percent of seabirds are already negatively affected by the waste problem. Go to the website and look at the pictures uploaded from around the world. The nests shown feature face masks, twine, plastic strips, and complete shopping bags in them. I look at these images and have a “that ain’t right” feeling that is confirmed when I study the sad picture of a dead egret with its legs twisted in twine. The Birds & Debris project is not one that you need to join or register for, but it is a good crowdsourcing project to know about, in case you happen to see a problem nest. Now that I’m no longer nest blind, I’ll be on the lookout!

More Wisecrackin’ / Less Egg Crackin’

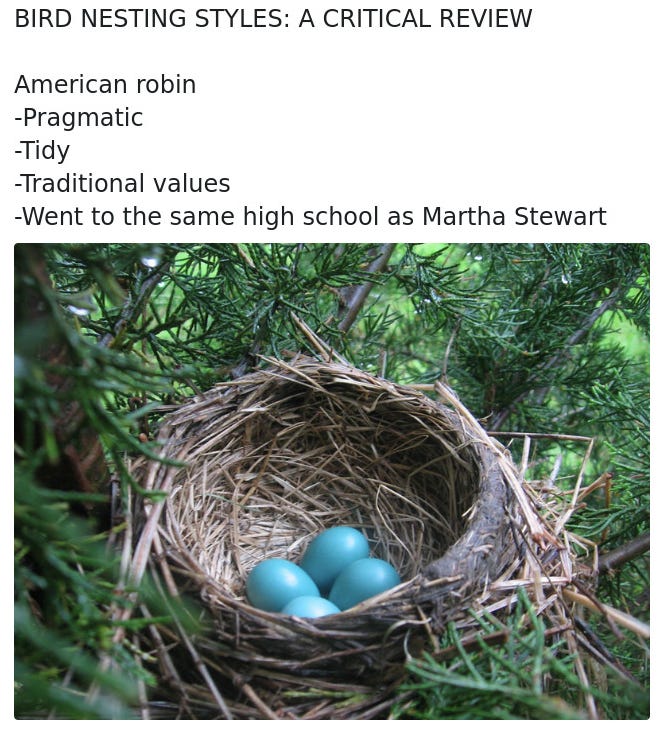

Where do you go to look for what’s hilarious about bird nests? The tweets on Twitter, of course. Ferris Jabr, who evidently is not one bit nest blind, reviews bird nests for degrees of style.5

Coming up in the next few issues:

More FrogWatch. More croaking.

Guest features, including a story about the app, iNaturalist.

City Nature Challenge. Mark your calendar as this is a one-day event. April 28. It happens everywhere you are if you have the app iNaturalist on your phone and are ready to open your eyes!

The hike was sponsored and led by wonderful guides from the Sandy Springs Conservancy. Check the website to learn all the fantastic things the group does for the community and see the calendar of future events.

Here’s to Unsuicide: An Interview With Richard Powers. Powers won the Pulitzer prize in fiction for The Overstory in 2019.

I am on the lookout for nests! thanks for the education, as always ❤️