Puerto Rico & Coral Reef Community Science

Not all héroes wear capes. Some wear snorkeling gear.

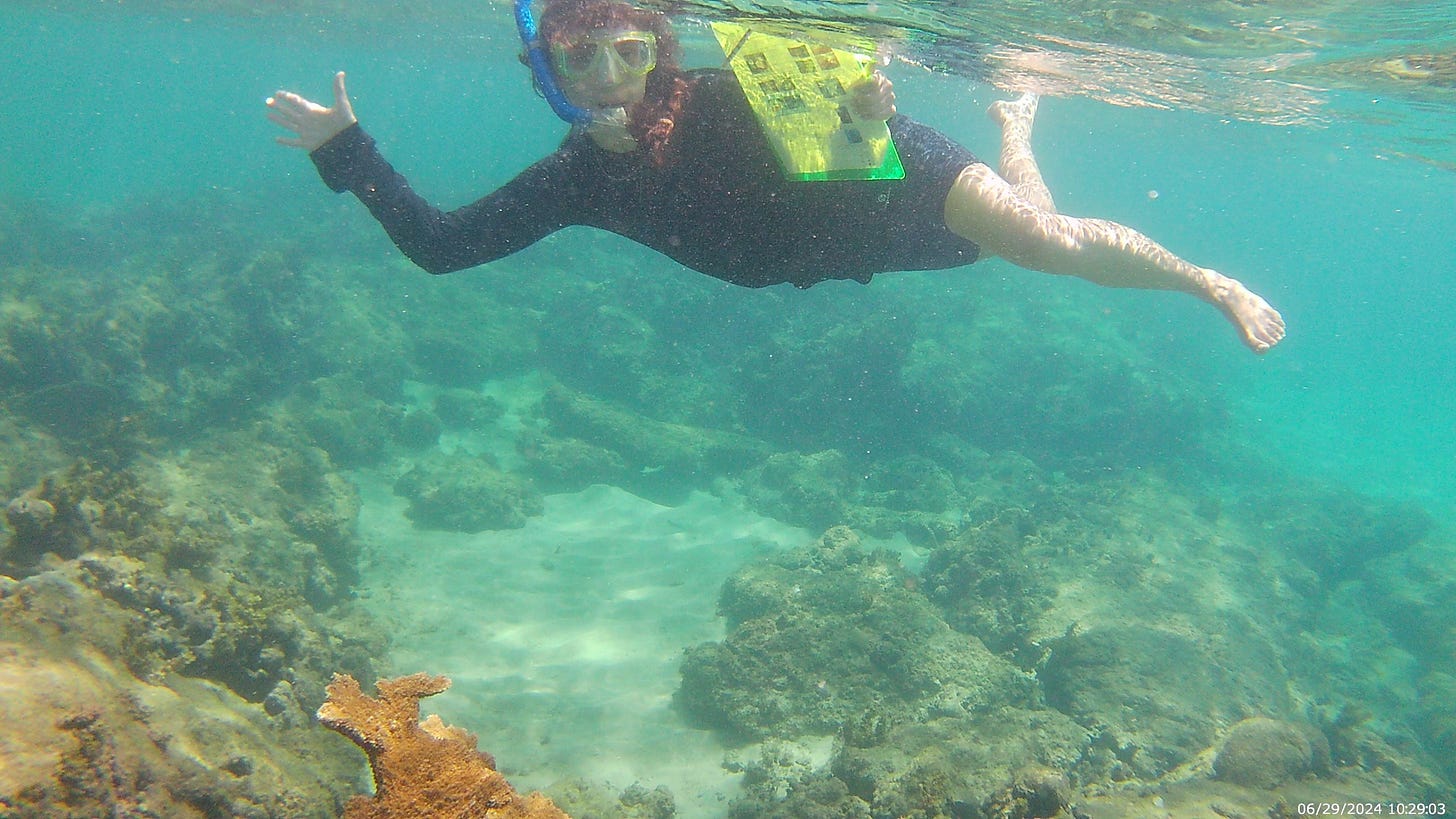

Every few weeks this summer, Puerto Rico resident Ariana Detmar has zipped on a wetsuit, crossed the warm sands near downtown San Juan, and waded into the ocean to volunteer as a community scientist. Her mission: to help protect one of Earth’s most biologically diverse and vital coastal defenders—coral reefs.

The data she gathers is crucial, say scientists who study these remarkable living organisms.

“We have already lost half of the world’s reefs, and scientists predict we could lose up to 90 % of them if actions are not taken to protect them,” says Dr. Elizabeth Mcleod, global reef lead at The Nature Conservancy. “Strategic, effective management is vital to supporting reef health and recovery.”1

Volunteers like Ariana are happy to be part of the solution.

Ariana assists with Puerto Rico’s Coral Reef Conservation & Management Program, a young initiative now powered by a committed group of 30 community science volunteers. I first heard about Ariana’s work through my daughter, Mackenzie, who has worked alongside her doing public health work in San Juan. Ariana’s day job is based in the public health field, working with data and modeling to understand local and global dengue transmission dynamics. Mackenzie and I have often talked about visiting PR to join Ariana on a reef check, a “one-day-soon” plan that lingered on our minds.

But lately, Puerto Rico has been in the news again, as certain political figures dismissed the island’s resilience and overlooked the island’s hard-won progress. Today, it feels more important than ever to share Ariana’s story—a testament to the dedication and steady work happening on the island that is considered by many to be a Caribbean paradise.

Reflecting on her work in community science, Ariana shared that while she understands the importance of gathering data to help preserve these vital reef ecosystems, the experience also brings her personal joy.

"I'm always in a happy mood when I know I get to go out for a snorkel to monitor the reef," she said in an interview. "I suppose I become aware of whatever stressors were weighing on me from work or life once I hit the water and start the five-minute swim out to the reef. I instantly feel calm, weightless, and serene in a way I don’t feel outside the water."

“We also help protect the coral because, in a way, they protect us too," she added. "When we take care of the reef, we’re taking care of our island’s future.” Scientists report that the ridges in coral reefs act as natural barriers, protecting the coastline and reducing wave energy by up to 97 percent.2

Listening to Ariana speak about the corals, the fish, and the delicate balance of the reef ecosystem filled me with admiration and hope. Enjoy the interview below, where she shares her unique brand of community science. I hope you’ll find what I found: a reminder of Puerto Rico’s strength and resilience, and a testament to how real change is built through connection, love, and action.

What inspired you to start working with the Coral Reef Conservation & Management Program?

I was taught to swim at a young age by my parents and have always felt at ease in the ocean. My mother is from Puerto Rico, so when we visited the island for family vacations, snorkeling was a central family activity we all enjoyed. Since moving to Puerto Rico last year, snorkeling on the weekends has become my favorite hobby. So when I found out about this volunteer program to collect data at the reefs I already loved to snorkel at, it was an easy decision to get involved.

What does a typical outing look like when you're working on a reef survey? Are there any challenges you often face? How often do you go out?

My boyfriend and I go out to survey our adopted reef roughly every two weeks. Our goal is to record key water quality data (pH, turbidity, surface temperature), general environmental observations (whether there’s visible runoff, trash, crowds, or water vessels near the shoreline), and document and assess coral health in a specific stretch of reef. We check for coral bleaching, signs of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD), and other indicators of reef health.

Our reef is located in San Juan, on a beach facing numerous threats—over-development, light pollution, high tourism, and storm drains, to name a few—yet it has shown resilience over the years.

Can you tell us a bit more about what the work is like, maybe paint a picture for us?

We swim about 300 feet out from the beach to reach the reef. I usually wear a rash guard and shorts to cut down on sunscreen use. My boyfriend uses fins, but I don’t.

In the Caribbean, the water is always comfortably warm, especially once the sun’s out. The warmth makes a big difference; if it were cold, I’d probably approach it with more hesitation and less joy. On calm days, the water is a clear, light turquoise near the shore, deepening to a richer blue as you swim out to deeper water.

In the morning, the beach is quieter, but by 10 a.m. on a weekend, it comes alive. There are families with children, people playing salsa or reggaeton from speakers, fitness boot camps on the sand, and surfers catching waves—it’s a lively mix of beachgoers and ocean lovers enjoying the shoreline.

And once you reach the reef, what is the process?

We start by visually triangulating to find our "start spot" on the reef. There’s a tall white condo building that we use as a landmark, swimming directly in front of it until we reach the reef. Once we locate a 50-foot sandy break between reef rocks, we know we’ve reached our starting point. From there, we swim west along the edge of the reef, snapping photos of corals with bleaching or SCTLD, especially those with distinct shapes, features, or surroundings, so we can identify them on future trips.

We also keep an eye out for lone dead urchins on the sand floor, as a parasitic disease is affecting urchin populations in the Caribbean and beyond, though I haven’t spotted any yet at the reef I monitor (https://www.npr.org/2024/04/17/1245366879/a-parasitic-disease-is-killing-off-sea-urchins-in-the-caribbean-and-the-sea-of-o).

Once we reach our "end spot," about 30 to 40 feet west of where we started, we circle back and monitor corals a few feet deeper into the reef, creating a rectangular box shape for our monitoring path.

After we complete monitoring and taking photos, we usually explore other parts of the reef for fun. Observing fish and feeling them observe us is incredibly therapeutic. Boxfish and trunkfish always seem the most curious about human visitors, often holding eye contact for long stretches. It’s always a special feeling to sense a kinship with another animal through eye contact.

In what ways have you seen the reefs change over time? Are there particular events or human activities that have had a significant impact on their health?

I’ve been participating in this program for about four months now. This summer, we’ve seen record-breaking ocean temperatures, and mass coral bleaching events are starting to be observed along the northern coast. Sea surface temperatures in our area have consistently been in the high 80s (86-89 degrees) for the past three months, and prolonged high temperatures like this cause coral bleaching.

Have you seen local interest and participation in the program grow?

This program has only recently restarted, but so far, the volunteer group is strong and additional trainings will be conducted later in the year to add more volunteers.

What are some common misconceptions people have about coral reefs or ocean conservation?

Many people don’t know that corals are animals, and although they play an essential role in marine ecosystems, they are constantly exposed to threats that endanger their survival. I think if more people learned about corals and local marine ecosystems, perhaps more people would actively work to conserve them.

Corals are really sensitive. Water vessels scraping or bumping into them can kill them, as well as inexperienced snorkelers touching them or kicking up too much sand around them. Many of the larger corals you see are hundreds of years old, so seemingly small actions can cause significant damage.

What role do you think community scientists like yourself can play in advancing environmental stewardship?

An appreciation for nature and environmental stewardship was instilled in me at a young age and remains important to me. I think that by sharing what I observe as a community science volunteer, I can help spark an interest in others to be more intentional about their own environmental stewardship.

As a side note, I think it’s great that the Department of Education of Puerto Rico requires elementary, middle, and high school students to log 10 hours a semester of nature-related and conservation activities on the island. Last weekend, I participated in a beach clean-up event at my adopted reef and learned about this program after talking to several high school students who were logging their hours.

If you could make one change to help protect Puerto Rico’s marine ecosystems, what would it be?

Sadly, the biggest threat to Puerto Rico’s marine ecosystems and reefs is climate change. This summer, sea surface temperatures broke records, and volunteers in my citizen science program are starting to observe mass bleaching events across the north side of the island. Corals expel symbiotic algae that provide nutrients and color when ocean temperatures rise. Algae can’t produce enough energy through photosynthesis at high temperatures, so they start producing toxins that can harm corals. If corals go too long without their algae and remain bleached, their polyps can begin to die. Since corals are crucial to the reef ecosystem, mass bleaching events like this could lead to ecosystem collapse.

Bonus recommendation from Ariana:

Before I go, I’d like to recommend the podcast La Brega to any readers wanting to learn something about PR. This podcast does an incredible job of explaining many facets of Puerto Rican culture and identity through the lens of history and lived experiences...and it is easy to listen to!

This is such a cool program! Thank you for highlighting it, Ariana's work, and the importance of PR.