Are You Ready to Talk About Mosquitos?

Me neither. But I will because community science is waiting.

Saturday evening about 5 p.m., Fred and I headed out to a local nature preserve to participate in the Great Southeast Pollinator Census. First, we picked up a to-go meal and found a quiet bench beside a stream to eat and look around. All was peace until the mosquitos flew in to join the feast, or at least one did. I saw him on my arm and real quick-like. . .

SLAP.

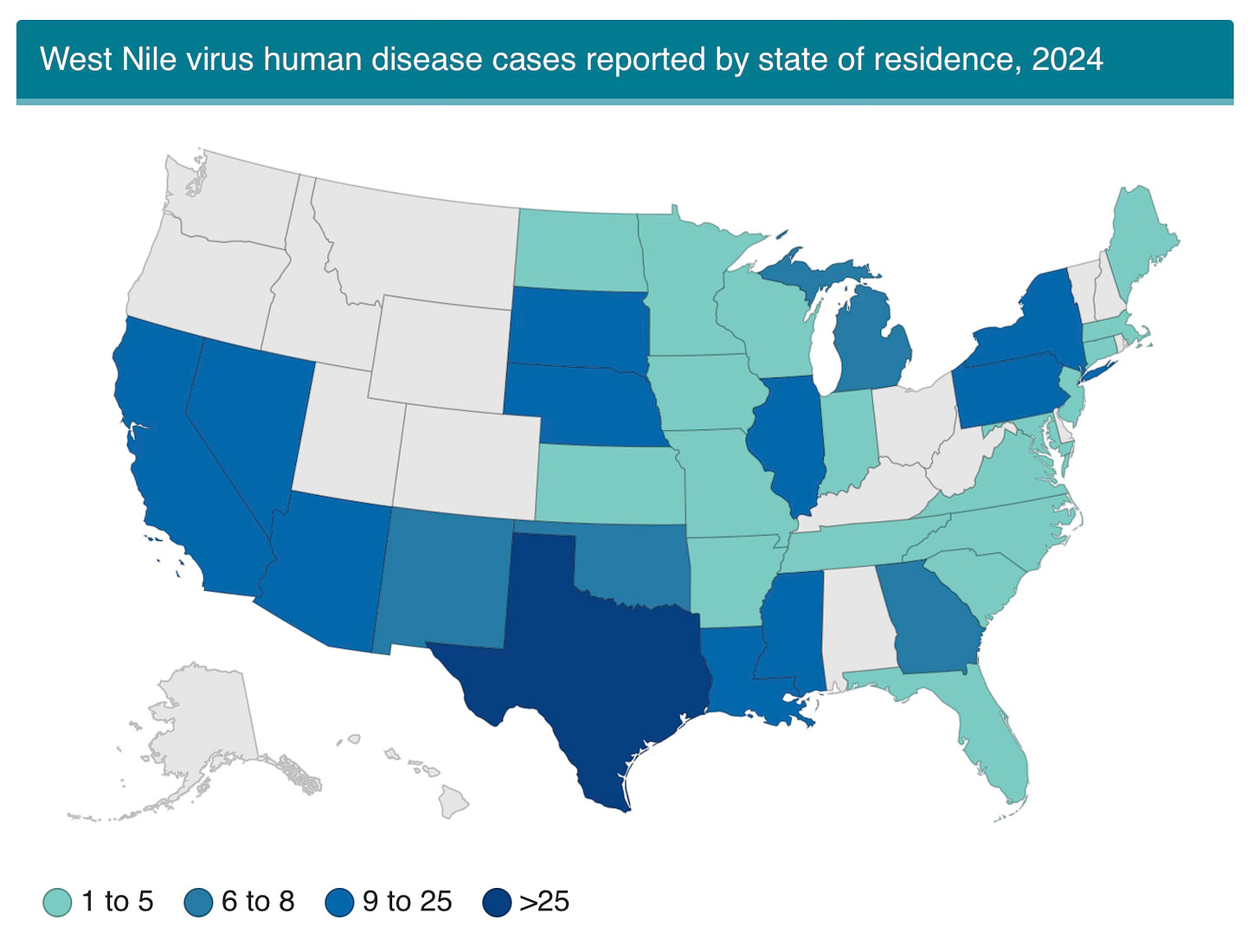

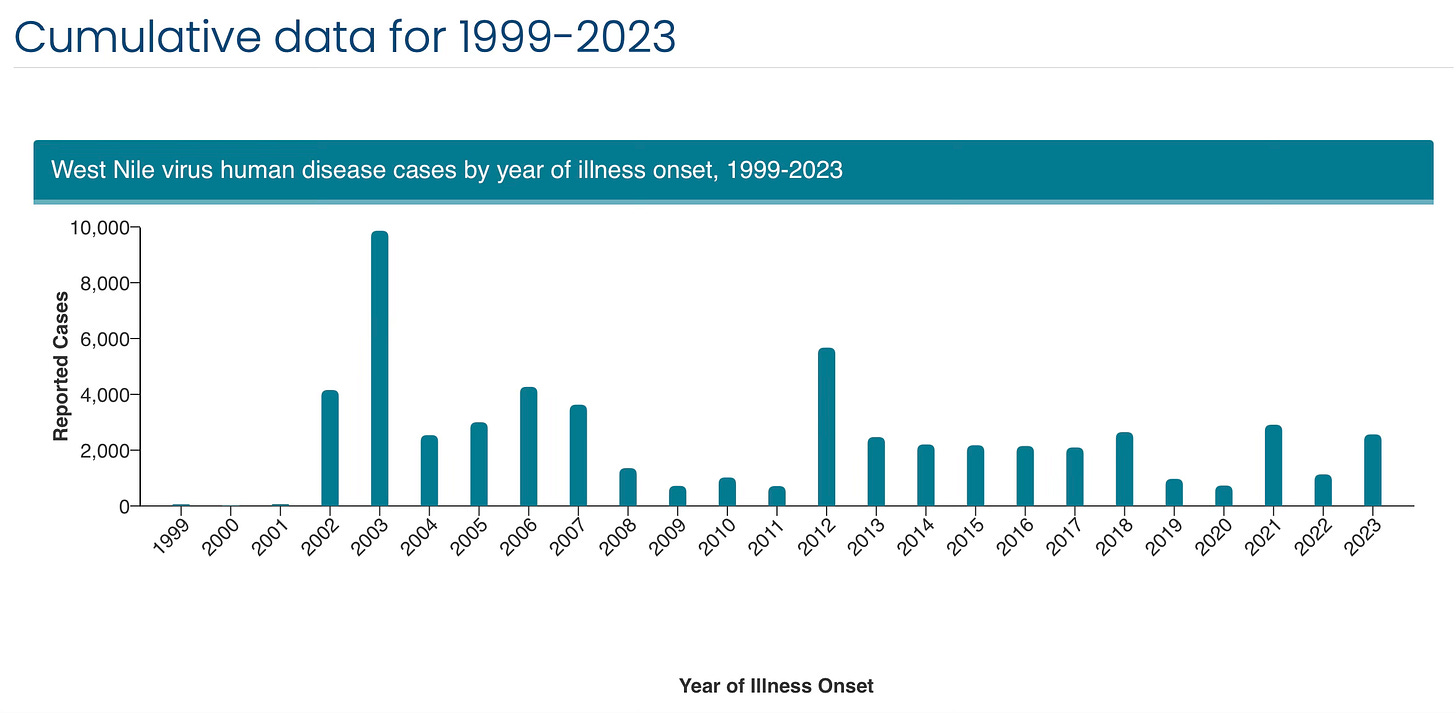

I got him, but he’d been there awhile. I showed Fred what happened and together we went yuck when we saw my blood. But that particular type of yuck––familiar to most of us––has become more worrisome lately because some mosquitoes are infected by the West Nile virus which can make people sick. There’s been an uptick in West Nile cases this month in many parts of the country.

From the CDC: West Nile virus is the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the continental United States. It is most commonly spread to people by the bite of an infected mosquito. Cases of West Nile occur during mosquito season, which starts in the summer and continues through fall.

There are no vaccines to prevent or medicines to treat West Nile in people. Fortunately, most people infected with West Nile virus do not feel sick. About 1 in 5 people who are infected develop a fever and other symptoms. About 1 out of 150 infected people develop a serious, sometimes fatal, illness. Reduce your risk of West Nile by preventing mosquito bites.

Also, there’s a new mosquito-related disease: eastern equine encephalitis (E.E.E.) According to experts, E.E.E. has a higher death rate and is more rare. It is not contagious from person to person. There is no treatment for the disease, and about 30 percent of people who get it die, according to the CDC. Many people who survive the illness have continuing neurological problems.

Globe Observer Mosquito Habitat Mapper

Despite these troubles, soon Fred and I will visit the Okefenokee Swamp for a few days. I asked the lady who made my reservations about the mosquitos and she said not too bad, but I didn’t follow up to find her frame of reference. So, we’ll be prepared with our long sleeves, long pants and plenty of organic and nonorganic bug spray.

While down in South Georgia, I plan to do some community science related to these little blood suckers. The Globe Mosquito Habitat Mapper project is a good one, sponsored by NASA. NASA offers a number of great app-based science projects, such as ones focused on trees, clouds, and land cover. I’m a big fan of them all.

I’ve never done the mosquito project, but after completing the tutorials in the app, I realize there are phases to the program. The first phase, which may be as far as I go for now, is to take photos of any standing water I see, either natural or artificial, which may contain mosquito larvae. I upload my photo and dump out the water if possible. If I want to go deeper with this project, I can scoop up any larvae I see, examine it, and provide more details to the app page.

But for now, I’ll keep things at the freshman level. Mosquito 101 for me.

The Okefenokee!

We are so excited to explore the Okefenokee. I plan to go all out on the community science projects down there at the swamp. Besides the mosquito work, I will go retro to revisit some old favorites like: Project Noise, iNaturalist project pages; and Globe at Night.

If you live in Georgia, you know the Okefenokee is so important to many here; some use the word legendary to describe this blackwater wetland. As homework before our trip, I recently listened to what must be one of the best explanatory pieces on the Okefenokee ever. Okefenokee Heavy & Precious is an article written, then read aloud by South Georgia author Janisse Ray. The piece ran in the Bitter Southerner, and is almost an hour long, but so worth it.1

The Okefenokee Swamp remains largely undeveloped compared to other major swamps in the United States, such as the Everglades or the Great Dismal Swamp and is a prime example of a functioning swamp, teeming with carnivorous plants, more than 230 bird species, floating peat islands, and an estimated 15,000 alligators.

We plan to paddle along some of these alligator-edged waterways. Wish us luck! We want to experience the swamp first hand, do community science, see the dark skies, and learn more about how the entire swamp may be threatened by the impact of a nearby proposed titanium dioxide mine. That last part is a depressing reality for the swamp.

Environmentalists and regular people have been fighting against the mine for at least the past 12 months, and it’s been a real rollercoaster of ups and downs. This summer a survey by the Southern Environmental Law Center found that 9 out of 10 Georgia voters oppose the mine, so that is good news, but this fight is far from over. Ray tells all about it in her podcast/article.

On a Brighter Note

When we go, we plan to stay a few nights in two different areas—Stephen Foster state park in a cabin, and near Folkston in an RV. Only $100 a night, but I think it is low season. Stephen Foster park is our state’s first-ever International Dark Sky park so that’s a big draw for us city folks. At night, we hope to gaze at endless stars accented by the Milky Way. During the day, we’ll take some guided tours into the swamp, go out on our own in canoes, and maybe do a little biking and hiking.

Also, if you’d rather read than listen, here’s a link to the text of Heavy & Precious.

Oh one more thing, wear head net to protect your eyes, ears, and neck. We wore those in Alaska and they were a life saver if you want to see!

Have fun! The boys went camping with Boy Scouts there a couple of times if my memory serves me correctly. Also, loved finding out that GA also has a Stephen Foster State Park. I've been to the FL Stephen Foster State Park, it's amazing and the pictures of GA also look amazing. I can't wait to hear all about it. Are you camping on a platform?