Spread the Silence

IT'S TOO LOUD! Help map the cacophony by using Project Noise's handy decibel meter. Contribute to sound pollution research.

When I wanted to learn more about the community science effort, the Noise Project, I headed into the city.

And, to the farm.

This farm in the city is the Metro Atlanta Urban Farm, a partner in the Noise Project. Located near College Park, Ga., I went there to use the Noise Project app to take decibel readings around the property.

The rooster, working the breakfast shift that morning, was cock-a-doodle-do-ing while I walked around, so I waited for his breaks to conduct the one-minute sound test. Decibel average: 67. Highest reading: 85.

Then I saw Bobby Wilson, farm co-founder and the person who oversees the place on a day-to-day basis. Wilson was there taking a break that morning, so we took a load off to rest and chit-chat on the workshed’s shady front porch.

Wilson, a retired UGA extension agent, told me all about the farm, how they give away produce to the neighbors in the summer, and gifted me a copy of the Farm’s 2024 calendar. (“Hey, you should write about us!”).

The property is located on Main Street less than a mile from downtown College Park. Wilson said he is cognizant of the street noise around his workplace, but also he forgets about it too.

“Yes, it’s true. Awareness is key,” he said. “Participating in the Noise Project has made me more aware of sounds, all of the background buzzing and noises we hear day in and out. I’m glad we’ve been a part of the project for so many years.”

Background on Project Noise.

The people who created the Noise Project, a community science effort funded by the National Science Foundation, are not cranky old-timers, but they do think the world is getting way WAY too loud.

And the din? It’s causing lots of problems. For example, sound pollution:

raises stress levels

interferes with learning

causes hearing loss

contributes to accidents

causes high blood pressure and moodiness

In a noisy world, you can’t even hear the birds singing which may be why Cornell Ornithologist researchers are collaborating with Project Noise to help find solutions.

Map a problem and you can visualize it.

Like many of today’s community science efforts, the Noise Project relies on a smartphone app. In this case, an easy-to-use decibel meter is built right into the free app.

I checked it out, and by now I’ve made around 30 readings. I’ll tell you how it worked for me, but, first the basics on how sound/noise is measured:

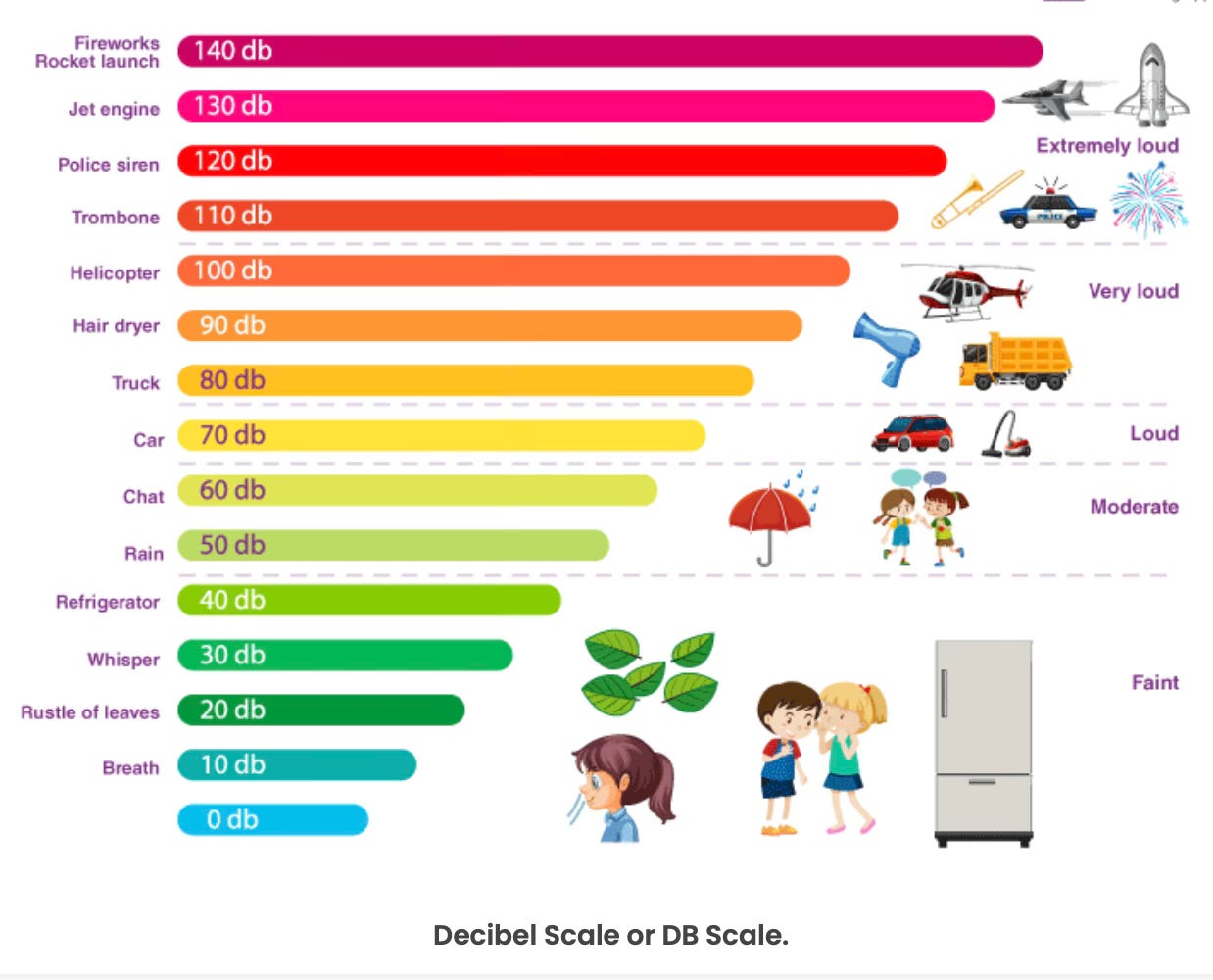

Noise pollution is typically measured in decibels (db), which are used to quantify the intensity of a sound. For example, a whisper is typically 20-30 db, normal conversation is around 60-70 db, and loud construction can be more than 100 db. The louder the sound the higher the number will be.1

As I got familiar with the Noise Project app, I checked out the decibel meter to understand how it works. My eyes gravitated to the green lines in the 20 db “rustle of leaves” level, because I’ve been out hiking so much lately searching in the woods for chestnut trees. But my big goal here was to focus on the less lovely yellow-to-orange ranges—-the 60 to 80 db readings I found in most parts of the city.

Using the decibel meter is easy: open the app, navigate to the decibel page, allow the app to record outdoor sound for minute, then select an emoji emotion (or two) to indicate how the sound makes you feel.

This last part, how noise makes you feel, is often overlooked. In the city, the echos of traffic, construction, airplanes and people are everywhere, taken for granted. Yet, there is a cost to background noise.

A 2019 Noise Project survey asked participants to “describe the way noise influences your mood.” The three most common answers?

Irritated.

Anxious.

Annoyed.

The survey also found, “people in our community have become desensitized to the noise around them. Many of us are not aware of the fact that noise can have a negative effect.” These findings imply that we almost don’t hear the constant hum of noise pollution which makes it hard for us to shield ourselves from harmful effects.

One researcher’s quote resonated: “. . . noise can just make you a more irritable person over time — even if you don’t realize it. Just constantly being exposed to that level of noise can make you less social, angrier and more impatient.”

The Noise Project, if successful, can bring the noise problems to light.

The screenshots below show what a Noise Project map looks. The yellow emojis represent the various sites tested, but of course mine were around Atlanta.

Congresswoman Nikema Williams (GA-5) is one person who is concerned about noise levels in neighborhoods. This year she reintroduced legislation to give communities more control to address highway noise. The Negating Neighborhood Noise Act legislation, co-led by Congressman Jim Himes (CT-4), would allow federal dollars to be used to build better and more innovative barriers along interstates near neighborhoods that existed prior to the interstate being built.

“Communities will also have the power to create noise barriers that are aesthetically pleasing and can be used for dual purposes, such as hosting broadband infrastructure or solar panels,” she wrote in a statement. “Highways I-20, I-75, I-85, and I-285 are some of the loudest, most disruptive interstates in the country and all run through neighborhoods in Georgia’s 5th Congressional district.”

I talked with a press secretary in Ms. Williams’ office, and she reiterated one important point. If the legislation passes, money will be available for older intown neighborhoods, not just new neighborhoods and new highway constructions.

In some areas of the U.S. and Canada, innovative sound barriers with solar panels built into them are being tried. See this and this. Solar panels used along highways can provide free or low-cost renewable energy to the homes and communities around them. Sounds like a cool idea to me. Would a low electric bill overcome the stress of a highway’s roar? Probably no, but still it could help remove the sting.

As always, community scientists can help.

I hope you’ll consider adding some decibel readings to the Noise Project map. The app is free to download, and you don’t have to make an account.

One feature of the app I love is the way users can create a Sound Refuge. To do this, you take a reading and if you get a low decibel score (think green and yellow-green), you can designate the spot as a Sound Refuge. Doing that gives the place a gold star on the map and others know to go there for some sweet peace and quiet.

Yesterday, I marked a Sound Refuge for the first time. This place, free and open to all, is along the Laurel Ridge Trail in the Smithgall Woods State Park near Helen, Ga. The reading I got there was 36 db, a score that would have been even lower, but for the lovely birdsong drifting down from the trees.

Additional reading:

The Community Noise Lab at Brown University.

Towards a Quieter City, The Philadelphia Citizen.

Which US cities are the noisiest? See Map. USA Today.

Cities Are Louder Than Ever — And It’s the Poor Who Suffer Most.

What No One Seems To Know About Honking in New York.

Extra content below for those who want to see the decibel reader in action. Trigger warning: a leaf blower is involved.

Decibels are different from other familiar scales of measurement. While many standard measuring devices, such as rulers, are linear, the decibel scale is logarithmic. This kind of scale better represents how changes in sound intensity actually feel to our ears. To understand this, think of a building that is 80 feet tall. If we build up another 10 feet, the building will be 12.5 percent taller, which would seem just slightly taller to us; this is a linear measurement. Using the logarithmic decibel scale, if a sound is 80 decibels, and we add another 10 decibels, the sound will be ten times more intense, and will seem about twice as loud to our ears.

I love that you wrote about this and told people about the decibel counter. As you know, my big complaint is that some business owners have made their spaces too loud in order to rev up excitement. I have wondered recently what hearing was like for people before the industrialized age, or whether people who have always lived in the country score better on hearing tests. In the meantime, People should take those meters to movies and loud restaurants and once they see the readings, ask the owners to turn it down. I wear earplugs so many places and hearing aids the rest of the time. What would be interesting is to invent a decibel reader for inner ears when people are using their headsets. I read the other day in AJC or somewhere those are what’s causing most hearing loss. Anyway, thanks for the article.

I don't think I realized how loud it was in the city until we moved to Oriental. We have the MCAS across the river at Cherry Point, so jet noise is an infrequent, but regular interruption to conversation. Highway noise is almost nonexistent. Mostly, we live in a very quiet place! I wonder if anyone has done a noise map near us???