The American Chestnut Tree

Science is involved in "rescuing" the tree. Results so far? They could be better.

Recently I interviewed environmentalist and Trees Atlanta employee Starr Whitten who told me a little about the history of the American chestnut tree. I’m a tree lover, yet I had missed this story, and the sad part about a blight that has destroyed virtually all of the species.

“Watch Clear Day Thunder,”1 Whitten said. “It’s a great documentary to help you learn.”

Seeing the hour-long show, I was hooked on learning more about the research and citizen science efforts going on to help bring back the tree.

That title, Clear Day Thunder? It struck me as odd. The documentary explained: folks would hear what sounded like booming thunder on a clear day. Soon they learned it was simply the crash made by another dying, blight-stricken chestnut tree falling in the woods.

Along with my cram course in American chestnut tree history, I’ve made a handful of field trips in middle Tennessee and around metro Atlanta to see young tree plantings. I now know there is a massive effort underway to bring back a version of a hearty and healthy American chestnut three, but success is still far from assured.

Forests have stories.

The overstory is the top level of forest growth, a canopy for the tallest of trees.

The midstory is shadier. Medium-sized trees grow here in an in-between world.

The understory includes shrubs, vines, and saplings growing at the forest floor.

The overstory

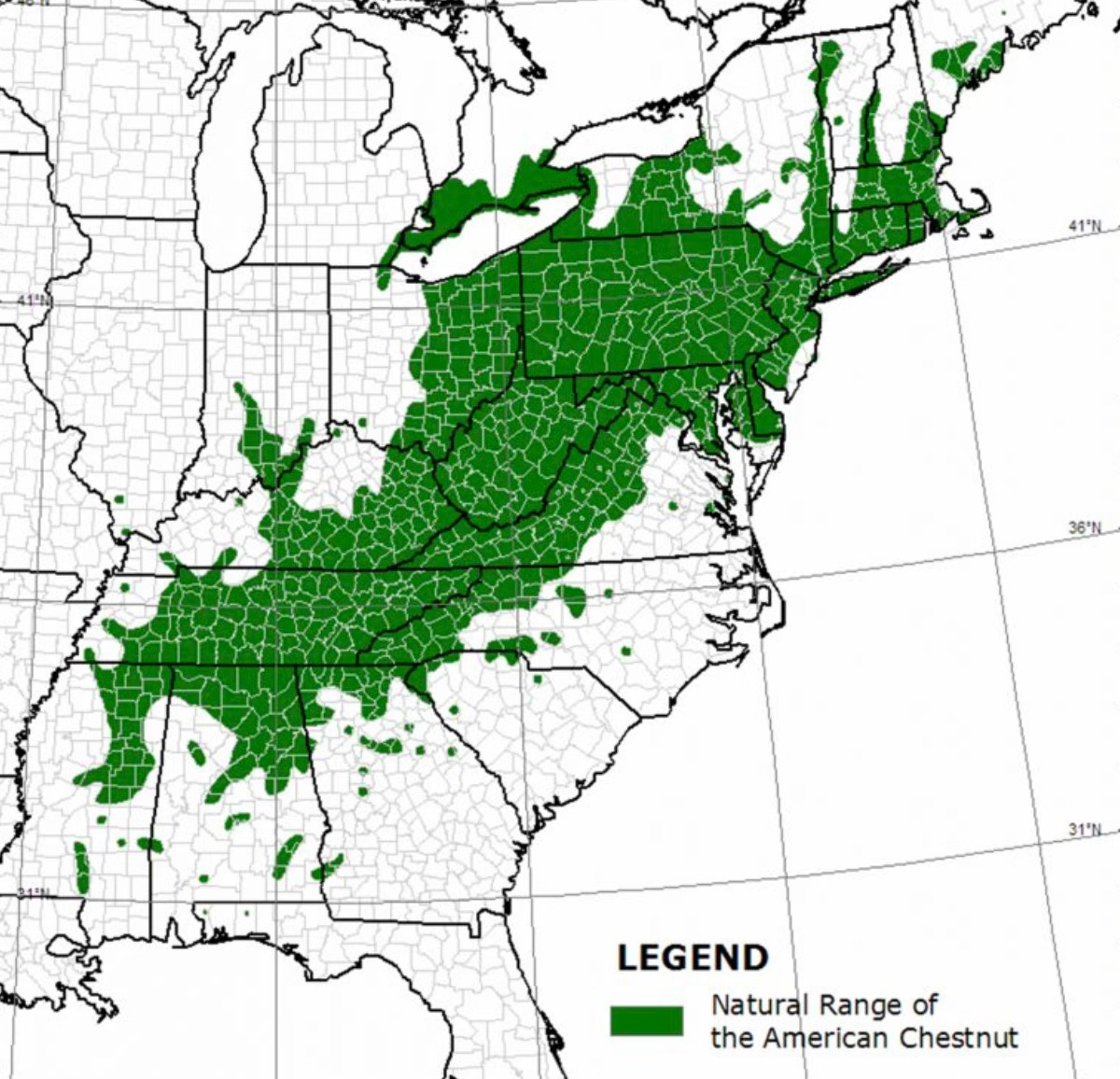

Just over a 100 years ago, the American chestnut tree was the dominant tree species in the eastern United States, flourishing for more than 40 million years. The trees were majestic, offering wood and shelter to forest animals, and the chestnuts were so bountiful they served as a crucial food source for both wildlife and humans.

The one-time popularity of chestnuts is indicated by the Christmas classic, “Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire." Tragically, the introduction of Chestnut blight around 1900 led to the near eradication of the American chestnut within 40 years.

Before the blight, scientists believe that one out of every four trees in the eastern U.S. was an American chestnut tree. The statuesque trees were so massive they’ve been called the “redwoods of the east.”

Now, they are virtually all gone. While some chestnut trees still produce new sprouts from surviving root systems, these sprouts are typically killed by the blight once they reach 8-20 feet in height, sometimes well before that.

Today, American chestnut trees are functionally extinct in the wild. Very few mature American chestnut exist in their former range, although many stumps and root systems continue to send up saplings. Most of these saplings get infected by chestnut blight, sometimes called cankers, which girdle and kill the trees before they reach maturity.

It’s sad. Few people living today have ever seen a mature American chestnut tree.

The midstory

The depressing fate of the American chestnut tree has not stopped tree lovers and scientists from trying to keep the species alive. There’s an active American Chestnut Foundation and chapters of volunteers in many states. To produce a healthy tree, scientists are creating hybrid trees that blend blight-resistant qualities from Chinese and Japanese chestnut trees into the original American species.

So far, results are far from successful. The hybrid trees don’t have the same tall stately shape as the American chestnut trees, the nuts reportedly don’t taste as good, and some are still susceptible to blight.

Citizen scientists are contributing to the effort. In West Virginia, members of the local American Chestnut Foundation plant baby hybrid chestnut trees near pure American chestnut trees.

The underlying idea is that these fragile tree saplings will gain strength and nourishment because they enter into a symbiotic relationship with underground mycelium, the plant mushrooms grow from. These shared mycelium nutrients may help reduce blight, but don’t seem to prevent the “cankers” from forming as the tree grows. Some treatments for the cankers are available but the solutions are far from perfect.

“Chestnutters,” the name given to those devoted to helping the tree, have not given up. Volunteers in West Virginia created a citizen science website for collecting observations and data to document the lives of these trees in all of their stages of growth.

Additionally, the world’s most popular and successful citizen science effort, based on the iNaturalist app, has thousands of volunteers helping with documentation. Not only is iNaturalist set up so that individuals can contribute data, but also there are also group efforts divided into “project pages” for special initiatives.

Today when I checked the site, I found some 13,000 individual American chestnut tree observations, 9,800 of which are research grade. Project pages are available for areas in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maine.

The understory

As I learned more about the history of the American chestnut tree, I kept ruminating on the wistful words I heard from the old-timers who talked about the trees of long ago.

My ruminations happened, I knew, because our brains are wired for tales, stories, and narratives. One researcher put it this way: “In the days before written language — most of human history, in other words — the only way to create an idea that persisted from one day to the next and spread from one person to another was to somehow make it durable in our minds (or “sticky”, to use a popular bit of marketing jargon).”

With that “stickiness” in mind, here is the understory—the foundation—that helped me understand all the fuss and effort being made for one single tree species.

People would gather there in the fall and I mean everybody. They’d get in the woods and gather them (chestnuts) in the fall and save them for winter, then roast them for Thanksgiving and Christmas. It was a treat for most Americans. In fact, my dad said (chestnuts) kept people alive during the Depression, there were still quite a few American chestnut trees alive then.” Tennessee park ranger.

“Schools would all turn out and let the children go out into the woods (to collect the nuts.)” American Chestnut blight documentary.

“Chestnut is quick. By the time an ash has made a baseball bat, a chestnut has made a dresser.” Excerpt from The Overstory, a Pulitizer-prize winning book about trees, especially the American chestnut.

“We really don’t have a clue of what it was like to have the entire American chestnut forest floor littered with this mountain of calories.” Speaker in Clear Day Thunder documentary.

“All in all it was nearly the perfect tree. Most every part of the chestnut yielded something. The most valuable product was probably the wood, but the most widely-known product was the nut. One chestnut tree would produce as much as three bushels of chestnuts—sometimes more.” Speaker in American Chestnut blight documentary.

“There is an old tale that you could walk through the woods in the fall in North Georgia during the 1800s and would be ankle deep in chestnut fruit.” Augusta (GA) Chronicle.

“A grove of chestnuts is a better provider than a man—and easier to have around.” Appalachian woman quoted in American Chestnut blight documentary.

“During the depression my dad and his cousin would load up the T-Model Ford with chestnuts and moonshine whiskey. . . and haul it to Washington D.C. to peddle chestnuts on the street and sell a little moonshine whiskey to wash it down with.” Speaker in American Chestnut blight documentary.

“People with no other cash income could depend on selling chestnuts to get their essentials.” Speaker in American Chestnut blight documentary.

You may be surprised what you find….Try a search: chestnuts “near me”

Clear Day Thunder is being shown during special community screenings. Upcoming screenings are: May 30, in Rome, Ga., and Aug. 19, Franklin, N.C. Check the link for more information.

I'm chasing down the documentary. Gotta see that!

Thanks for sharing this most interesting facts and history of the Chestnut Tree. I’m excited to share your newsletter with others I know will enjoy!